Luis A. Pacheco

Originally published in Spanish in La Gran Aldea - Translated by the author

"In the beginning, we were only six workers. But then there were hundreds. The news spread everywhere, and the company hired people to work. On donkeys, mules, ox carts, canoes, and trucks, they came to see the oil lake and look for work. It was something sensational."

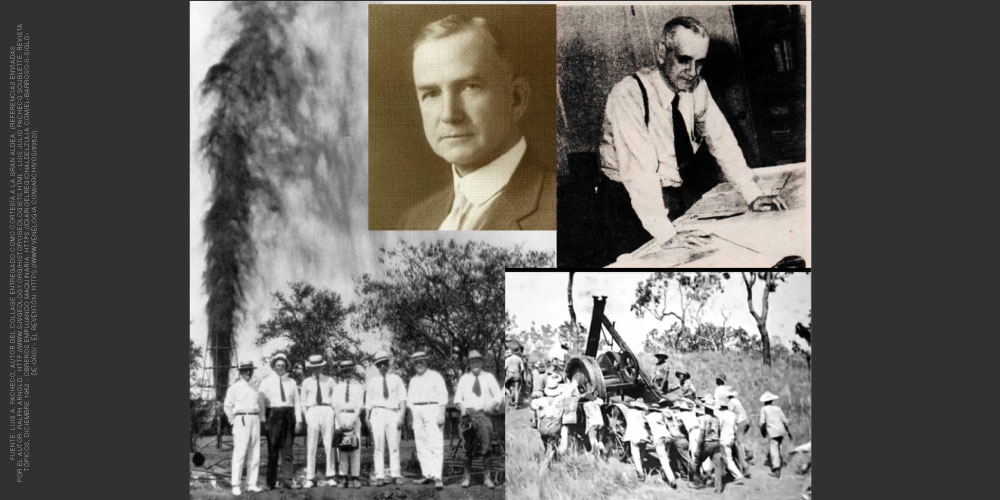

Alcibíades Colina, Barroso drilling crew No. 2 – Shell Topics, December 1952.

During my childhood and then adolescence, my grandfather, Luis Julio Pacheco Soublette, appeared to me like a grand old man always dressed in black, never a bad word, very religious. One of the things I regret about my childhood is being unable to sit down with him and ask about his adventures, as a young engineer, in Venezuela at the beginning of the 20th century. Those are the times that North American geologist Ralph Arnold described in his essential geological memory "The First Big Oil Hunt."[1]

This deficit in my childhood is an example of the ambiguous relationship that most Venezuelans have had with oil and its "wardens": we are as a nation a direct product of the exploitation of that resource, but we grew up demonizing it or, at best, being indifferent to it.

In his exploration diary, Ralph Arnold describes Venezuela as a backward territory without roads and riddled with tropical diseases. A country ruined from the continuous wars of the 19th century, on whose rubble the General Gómez hegemony began the creation of a national state.

The General Asphalt Company hired Arnold and his friends to carry out one of the most important exploratory campaigns in the world oil industry.

The territory assigned to the Arnold campaign covered the northern part of Venezuela and southern Trinidad during the period between 1911 and 1916. With one exception, none of the geologists who accompanied Arnold spoke Spanish.

Arnold reports in his chronicle, written fifty years after the events, the participation of some Venezuelan professionals in that great hunt:

"Venezuelan engineers varied between those who were excellent and full of energy and others who were less ambitious. Among the engineers in eastern Venezuela, we will mention Rafael Torres, Santiago Aguerrevere, Enrique Jorge Aguerrevere, Pedro Ignacio Aguerrevere, Martín Tovar Lange, and Luis Julio Pacheco, whom I consider capable and conscientious workers."

Being just a footnote in history would not bother those young engineers (and many other anonymous actors), who undoubtedly considered Arnold's campaign an adventure, better paid or at least more exciting than the alternatives in a country with few opportunities.

Arnold's first report in 1912 found few takers in the United States. However, in Europe, Sir Henri Deterding, president of Royal Dutch Shell, showed interest in the Arnold report and decided to pay the sum of ten million dollars for 51% of the General Asphalt Company's interest in the Caribbean Petroleum Company, which controlled interests in the exploration territories in Venezuela.

On June 12, 1914, the Caribbean Petroleum Company began drilling the Zumaque 1 well in Mene Grande on the eastern shore of Lake Maracaibo [2]. The well was completed in July of the same year, producing 260 barrels per day.

I ask the reader to go back in his imagination to this era: few roads, water transport, pack donkeys and draft oxen, percussion drills, drilling towers made of wood from the surrounding jungle, malaria, zero medical services, etc.

Between 1911 and 1916, Arnold visited Venezuela six times, but only for short periods, given the country's inhospitable conditions. During World War I, most of the oil activities in Venezuela came to a halt.

So, we will pick up our story in 1922. Although Arnold had long since finished his reports, he had identified the eastern shore of Lake Maracaibo as a prospective area, hence the discovery of the Mene Grande Field.

As part of the exploratory campaigns in the Cabimas area (also in the eastern shore), the Venezuelan Oil Concessions [3] had drilled several wells: Santa Bárbara I (1913), which turned out to be dry; Santa Bárbara II (1916), which produced some oil; and Barroso I, which was also dry.

In May 1922, operations began at the Barroso II well in the vicinity of Barroso I.

The account relates that, like most significant discovery wells, the Barroso II had operational problems. The drill (a percussion rig) got stuck, and the drilling stopped. An expert - some accounts talk of a spare part - that the company had to bring from abroad finally managed to free the drill. But, unbeknown to the crew, the drilling pipe was serving as a mechanical plug. What followed was the Barroso II blowing out early December 14, 1922.

Today, the blowout would only be news as an operational accident. However, in those days, word spread worldwide, confirming the oil potential of Venezuela that Arnold had documented.

Much has been written to discuss the impact that this event had on the world that was waking up to the oil century, but on Venezuela and its subsequent economic and political development throughout the 20th century and so far in the 21st century.

This event, like oil and gas in general, has been the subject of a "gold" legend and a "black" legend. There is no deficit of opinion on the pernicious or modernizing effects of oil, and indeed my attentive reader will have, on this centenary date, many a paragraph from which to choose.

But I digress. Let me go back to my conversational deficit with my grandfather. In December 1982, my stepfather, Carlos A. Rico, also an oil worker, sent me a copy of Tópicos magazine, the communication vehicle of Maraven S.A.[4] In that magazine, in its December 1952 edition, the thirty years of the Barroso Blowout No.2 were commemorated. The magazine interviewed some of the workers at the blowout still alive: Alcibíades Colina and Samuel Smith, from Cabimas and the Concepcion, respectively, and Luis Julio Pacheco Soublette, from Caracas.

In the interview, Luis Julio shares his memories of the "blowout":

"Since a well of such magnitude and with such power was not expected, there were not enough elements available for proper control, transportation, and storage. Consequently, the main task consisted of opening firebreaks and storing the greatest amount of oil in a natural earth tank, building a wall in the natural or saline depression between Cabimas and La Rosa, where a considerable amount was deposited. At the same time, we laid pipes and assembled pumps and boilers, and we built a temporary dock to be able to ship the oil since in La Rosa, there was only one tank of 55,000 barrels, that is, half the daily production, which was estimated at around 100,000 barrels".

How could it be possible that no one had told me this? I thought. How come that: the person who taught me how to knot my tie; the one who anonymously walked to El Recreo parish church for daily mass; who spent his mornings doing crossword puzzles; who whimpered when something got lost, would have participated in the epic event that changed the course of history for us, and never bragged about it?

Where were the heroic anecdotes, the fights with mosquitoes clouds, the opening of paths at the point of a machete in unexplored jungles? If he had been English, he might have left a diary. But for him, as for his companions, it was just a way to earn a living.

Suddenly, the dusty library in his house in Sabana Grande in Caracas, with its treasure trove, made sense: the theodolite, the binoculars in their faded leather case, the T-rule and protractor, the explorer's helmet, the Jungle Jim style knife, the pearl-handled revolver; everything had a story to tell but no audience. The story of the men and women who invested their lives and affections in search of the idea of modernity that the oil industry has always symbolized never had a proper narrator.

Luis Julio, my grandfather, worked with Ralph Arnold and was at the Barroso No. 2. It became clear his protest when president Rafael Caldera, in 1971, announced the Oil Reversion Law: "Rafael, you are going to destroy the industry!" he yelled at the television. But, of course, I, like most Venezuelans, did not understand the context and did not pay attention.

I wonder if one is born with destiny one is forced towards or shapes it while walking. As you may have deduced from this story, I come from a family (grandfather, father, brother, nephew, father-in-law, wife) who lived around oil. Still, for them, that was how they earned their keep. From a very young age, I decided not to be part of that industry for reasons I can't remember. However, the turns of life brought me to my place of origin. Like my grandfather and the rest of my family, I ended up being an involuntary actor in a story yet to be written. However, Luis Julio's life at the turn of the century must have been more adventurous and adventurous.

It is the 100th anniversary of the blowout of the Barroso No.2 well. An event far away in time, in a mysterious tropical land full of challenges and opportunities. We were once a backward nation that aspired to join modernity guided by the hands of exceptional people – who didn't think they were making history, just working. In this century that desires to see the end of fossil energy, let us remember the civil heroes of our oil industry, Venezuelans and foreigners alike, builders of civilization.

To Luis Julio, my grandfather, how I regret not knowing what to ask.

References

1. The First Big Oil Hunt: Venezuela, 1911-1916. Vintage. New York, 1960.

Andrés Duarte Vivas commissioned a Spanish translation of this essential testimony: "Primeros Pasos. Petróleo en Venezuela, 1911-1916" Ralph Arnold, George McCready and Thomas Barrington. Fundación Editorial Trilobita, 2008. ↑

2. This is where President Carlos Andrés Pérez decided to carry out the formal act of "nationalization" on January 1, 1976 – an important political symbolism. ↑

3. Venezuelan Oil Concessions Ltd. (VOC) was an oil company established on May 23, 1913 in Venezuela to operate the concession given in 1904 by the government of Cipriano Castro to Antonio Aranguren in the Bolívar and Maracaibo districts of Zulia state. This company came under the control of Royal Dutch Shell (Caribbean Petroleum Company) in 1915 ↑

4. Maraven S.A. was the name given after the nationalization of the oil industry in 1975 to what had been Shell de Venezuela, heir to the Caribbean Petroleum Company. ↑

Note: Carlos Oteyza's documentary - El Reventón. The beginnings of oil production in Venezuela (1883-1943).